Keystone Species

If you’ve been immersed in the native plant world for any length of time, you’ve undoubtedly heard the phrase keystone species. You probably have even figured out that it means the plants assigned that phrase are especially important. But why? This is the second post in our ongoing series about phrases we hear and use a lot as native plant professionals but may not always take the time to explain fully. “Keystone species” is a phrase used in almost any conversation we have with folks wanting to put more native plants in their yards. Let’s take a look at what it means.

Keystone species define the ecosystem in which they’re found. Often, an ecosystem wouldn’t exist without a specific species to anchor it. These species are of singular importance; if one disappeared, there wouldn’t be another species of similar ecological value to take its place. Simply put, keystone species are essential.

Keystone species aren’t necessarily the largest species in an ecosystem or the most prolific or abundant, but they have an incredible influence on the surrounding food web and ecosystem. Any living organism can be a keystone species. Something fun to think about is that keystone plants work as attractants for keystone pollinators and other insects - this is known as keystone mutualism.

For the sake of simplicity, we’ll focus on keystone trees and plants (that support keystone insects and animals!) in our ecoregion, the eastern temperate forest.

Ohio’s Keystone Trees

Ohio is part of the eastern temperate forest ecoregion, characterized by enough precipitation to foster tree growth in most areas, with humidity that varies daily but can be expected year-round. Most of the United States population resides in this region, including the entire eastern U.S. Except for two small pockets in California, our ecoregion has the highest plant diversity of all the United States and Canada regions. We are so lucky to live in an area where we can see and plant so many trees and plants that are both beautiful and beneficial to our local ecosystem. Let’s look at some keystone tree species we can enjoy here in Ohio. If you want to plant a native tree in your yard this season, keep reading for information on the three genera with the most ecological impact.

Oaks (genus Quercus) are the trees that benefit wildlife most in our area. All native species of oak are host plants for over 400 species of butterflies and moths. These butterflies and moths deposit eggs on oak leaves, and when the caterpillars hatch, they eat the oak leaves. Can you imagine seeing 400+ different types of butterflies and moths in your yard over a season? It would be incredible! Also, have you ever seen an oak tree looking ratty because it’s being used as caterpillar food? Neither have we! Oaks and other native plants can withstand this type of “pest pressure” and will continue to grow new leaves - they’ve evolved alongside these insects and have adapted to them.

Butterflies are important insects in their own right, and their caterpillars are a crucial part of the food web. Nesting birds feed their young almost exclusively on caterpillars, and a nest of 4-6 baby birds needs hundreds of caterpillars each day to survive and thrive. Think about how many caterpillars one mature oak can provide food for and the cascading effects of these caterpillars feeding birds and growing into pollinators. It’s easy to understand why oaks are a keystone species.

There are oaks in this region ranging from 12-25 feet tall to the typical giant, sprawling oaks we often think of. The photo gallery in this post includes infographics on a couple of our favorite, smaller species that would grow well in urban and suburban yards.

Trees in the Prunus genus, like black cherry (Prunus serotina) and native plum (Prunus americana), are also keystone trees. They provide food for almost 350 species of caterpillars, flowers that provide nectar for insects, and fruit for many types of birds and other animals. They are beautiful trees and shrubs for nearly any yard, with varying light, soil, and sun requirements. There are many native Prunus species to choose from, and each one provides crucial support to the surrounding ecosystem.

The third genus in the trifecta of amazing keystone trees is the Salix genus - familiarly known as willows. Black Willow (Salix nigra) and Pussy Willow (Salix discolor) are two well-known species that are native to Ohio. Black Willow trees are commonly found along pond margins and stream banks and are excellent at shoring up erosion-prone areas and preventing flooding. Black Willow grows to an average of thirty feet, with multiple trunks. Pussy Willow is known for its catkins and can grow in a similar environment to black willow. It is a clonal species, which means it can form dense thickets if allowed. It can also be a single specimen plant in a landscape. All willows are host (food) plants for the caterpillars of nearly 300 butterfly species. Their early bloom time provides critical pollen for native bees just emerging after winter.

Keystone Plants of Ohio

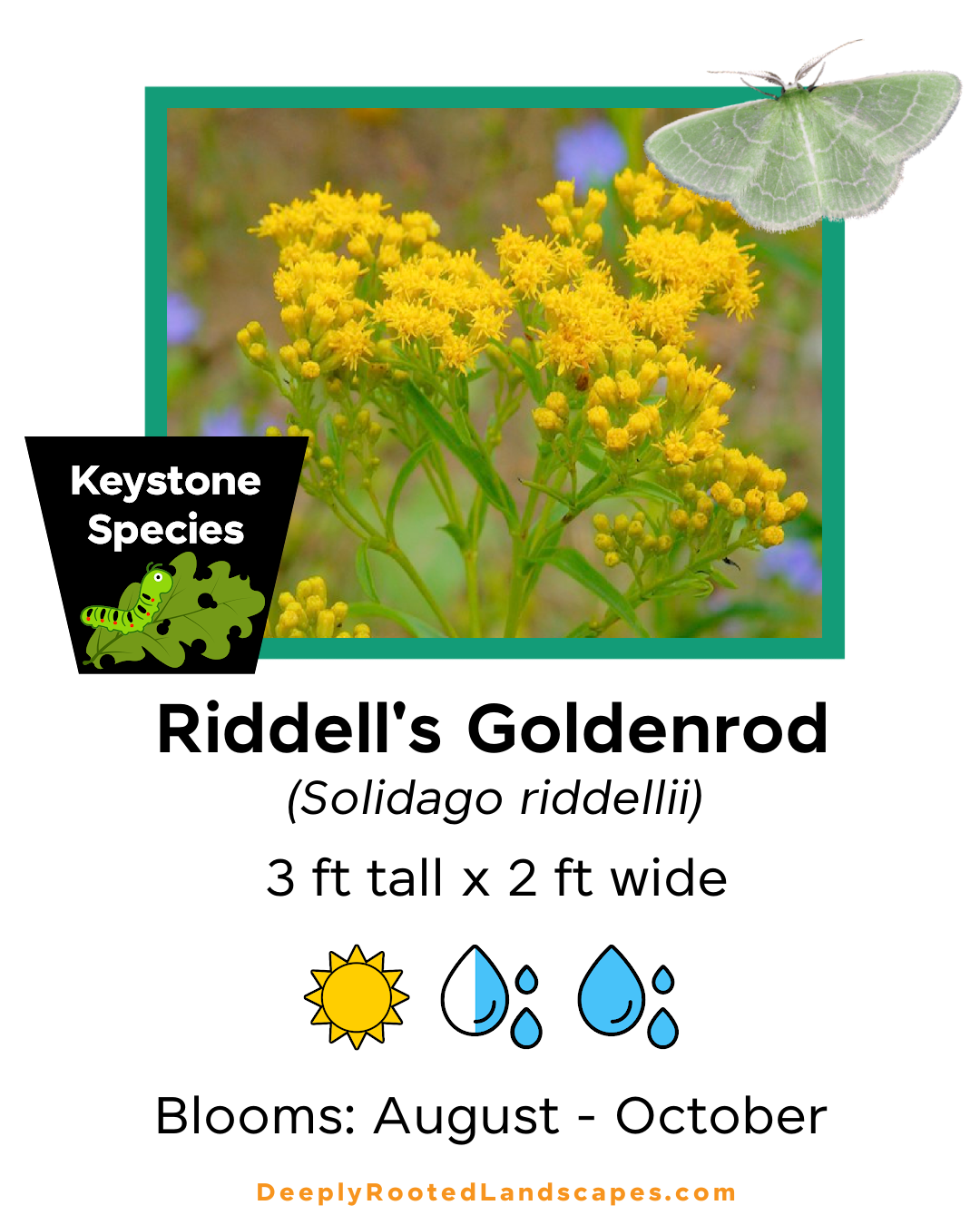

Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) is at the top of the list of keystone plants for Ohio, serving as a food source for over 100 species of caterpillars and more than 40 species of native bees. Many people know exactly two “facts” about goldenrod: it’s invasive and causes horrible allergies later in the season. Fortunately, both of these oft-repeated “facts” aren’t true! While Canada Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) can spread quickly, using rhizomes to expand its reach, it’s native to Ohio and is not an invasive species. If you’re worried about Canada Goldenrod being too vigorous a grower for a smaller garden, you’re in luck: there are many, many other species available to choose from. Gray Goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis) is a slow-growing, shorter-statured goldenrod that looks wonderful peppered among native grasses. Blue Stem Goldenrod (Solidago caesia) loves a shadier spot and is beautiful planted next to Blue Mistflower (Conoclinium coelestinum), which blooms at the same time.

As far as goldenrod pollen is concerned with fall allergies, luckily, this is also untrue. Many people confuse ragweed, the actual allergen, with goldenrod because they bloom at the same time. But goldenrod pollen isn’t windborne - it’s too heavy! It is heavy and sticky and sits on the plant, waiting for one of the many native bee species to move it to another plant or use it as food.

Goldenrod is an insect magnet, attracting butterflies, moths, bees, and wasps. It attracts predatory and parasitoid wasps, which is excellent news for gardeners dealing with pest insects. Growing plants like goldenrod will create a habitat for these beneficial wasps, offering you free, safe pest control in your garden and surrounding yard.

Asters (Symphyotrichum spp.), like goldenrods, are essential to insects and, thus, the food web. Over thirty native bees use asters for food for themselves and their young. One hundred butterflies and moth species have asters as their host plant (food source). They are one of the latest blooming native plants in Ohio, and they bloom from September through November. Asters are an excellent substitution for non-native mums and can be planted in a porch pot and cut back mid-season to give them a shrubbier, fuller look, with dozens of blooms per plant. New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae), Smooth Blue Aster (Symphyotrichum laeve), and Heart Leaved Aster (Symphyotrichum cordifolium) are especially showy.

Keystone species provide food for 90% of the caterpillars that become a critical food source for birds. Sunflowers (Helianthus species) host over 60 species of butterflies and moths. They also are a crucial nectar and pollen source for 50 different species of native bees. As the seeds ripen, birds and animals eat and store them away for winter meals. There are sunflower species ranging from very tall (8’ or so) to just a few feet and for full sun to shadier spots in the garden. A favorite is Downy Sunflower (Helianthus mollis), with its slightly fuzzy, light green leaves. All of the native sunflowers are branching, offering many flowers and then seed heads for insects and animals to choose from.

Your Yard Is Habitat

As evidenced above, keystone species are incredibly important to the health of an ecosystem. But remember, every native plant serves a purpose in its environment. For instance, milkweeds (Asclepias species) are critical to the survival of monarchs, but they aren’t a keystone species. Keep planting them! It’s wise to try our best to plant the most beneficial species we can, but every native plant in an ecosystem plays a role, and those roles fit together to create a vibrant wildlife habitat. Remember these keystone plants when planting your garden, and fit them in as you can. If you have a limited space, these might be the plants you focus on. If you have more room and haven’t planted an oak yet, please ask us here at DRL which oak might work for your yard. Do what you can, as you can: all habitat is helpful!